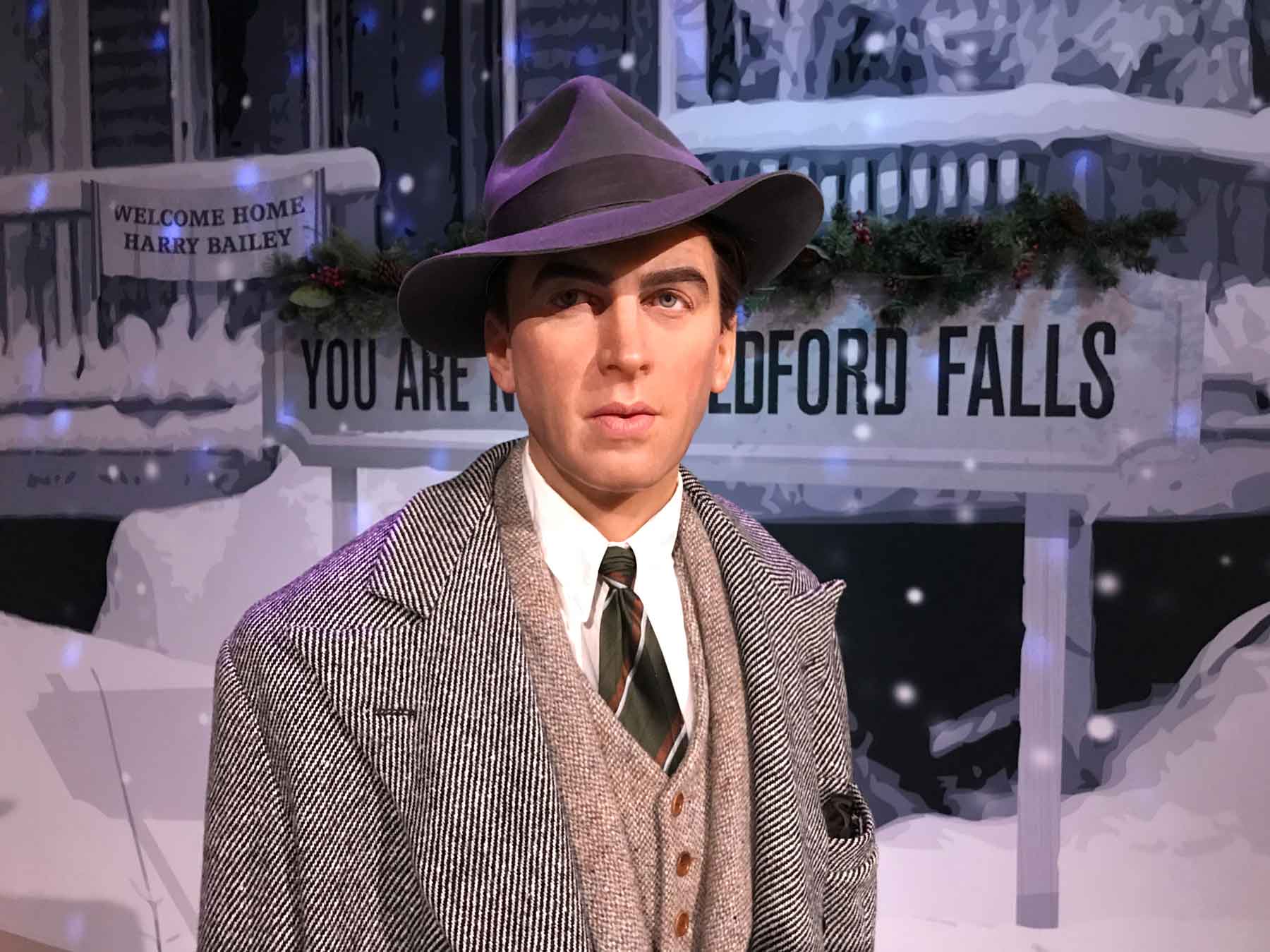

Markets had a wild end to the week but despite Friday’s down session, the S&P 500 advanced 1.43% this week. The Nasdaq Composite gained 4.41%. It was the Nasdaq’s best week since Jan. 13. But Friday’s slide pulled the Dow into negative territory for the week, finishing 0.15% down. It was an unsettling week for bank stocks and having spoken to many of you I sense there is a lot of anxiety. Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse is not a repeat of 2008. This week’s update will focus entirely on why I believe that to be the case. I will break down my reasoning using quotes from one of the best known films with a bank run, It’s a Wonderful Life.

We saw over and over this week governments and other financial institutions come to the aid of the banks facing heavy client withdrawals. The trend started Monday morning when the FDIC, Treasury and Federal Reserve came together to backstop deposits at Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank. Then the Swiss government provided similar support to Credit Suisse. Finally, later in the week, the major banks including JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, Wells Fargo, Citigroup and Truist came through with a $30 billion infusion to help the struggling First Republic Bank. Having 4 financial institutions needing assistance all at once understandably has many of you concerned, as it invokes memories of 2008. A little context I believe is necessary when looking at the turmoil in the market. First, SVB is the 16th largest bank in the U.S., and Signature Bank was a significant lender in the cryptocurrency industry. While they are the biggest banks to fail since the financial crisis, they are not the only banks to have failed. According to FDIC figures since 2009 513 regional banks have failed. So this is not a unique event, no panic ensued after those bank failures. It’s true that SVB was a bigger lender than any of those banks, but the reason markets are overreacting the way they are is timing. The failure happened at a time when investors and depositors are looking for signs of recession and are already fearful. That is why it was important that on Monday morning to help limit fears of a contagion, the Fed, Treasury and FDIC acted swiftly. They made good on all depositors at both failed banks, including customer deposits above the FDIC insurance limit of $250,000. The Fed also set up a new lending facility to provide loans to help ensure banks can meet their depositors’ needs.

SVB was much more susceptible to a bank run than a typical bank because unlike George Bailey’s bank their depositor base was not a diverse base of everyday people like your typical regional/community bank. SVB had a concentrated customer base, with deposits from startup tech and healthcare companies that received funding from venture-capital firms. SVB’s deposits more than tripled between the end of 2019 and the first quarter of 2022, as low interest rates drove a boom in funding for tech startups. The unique client base is evident by looking at SVB’s percentage of uninsured deposits (those exceeding the $250k FDIC insurance limit) relative to other banks. The bank’s uninsured deposits were 88% of their overall deposits. They derived those deposits from a particularly interconnected niche, venture capital firms. So when one firm said we are pulling their deposits others quickly followed. By contrast, the largest banks have significant capital requirements and a diverse depositor base. None of the large banks are even remotely close to 88% in uninsured deposits. JP Morgan holds 59%, Wells Fargo holds 37%, Bank of America holds 32%, and Citibank holds 31%.

In 2008 banks were playing with money they didn’t have, using more leverage and taking risks that they weren’t properly capitalized to handle. Almost all the banks in 2008 were taking excessive risk and had huge credit losses from bad loans and derivatives (credit default swaps) as the housing bubble popped. In contrast, SVB faced a sudden liquidity crisis when many depositors wanted their money all at once, an old fashioned run on the bank. SVB is a case of one bank growing super fast and not understanding how to properly hedge their interest rate risk. SVB got the majority of their deposit during the zero interest period of the pandemic. They invested most of these deposits in bonds. As interest rates rose, bond prices fell and venture-capital fueled funding came to a screeching halt. As a result, their deposits declined sharply. SVB needed to raise cash and had to sell its bonds at a loss to do so. The problem is uniquely tied to the bank’s poor interest rate risk management and its unique customer base. Most banks do a much better job hedging their interest rate risk and the big banks are stress tested regularly.

If you’d like to speak about your investments or your plan, my calendar link is below and you can schedule a phone or zoom appointment at any time.